The Last Podcast Post We Need to Write

The macro picture surrounding podcasts is pretty astounding. There are now hundreds of thousands of podcasts globally with total downloads now over a billion. On a monthly basis more than 1 in 5 US adults listens to at least one.[1]

This penetration has kept podcasts on the radar of the industry’s Marketing teams for years. And while I understand that inclination, I think it’s about time to admit that the industry as a whole has been unsuccessful in leveraging podcasts as a client engagement tool.

First, consider current deployment. I indexed the 20 largest firms via a simple question: does the firm have an active podcast that can be found on iTunes? Note that I excluded firms with a significant direct channel (e.g., Vanguard and Fidelity) and defined “active” (generously) as having published at least once in the past 6 months.

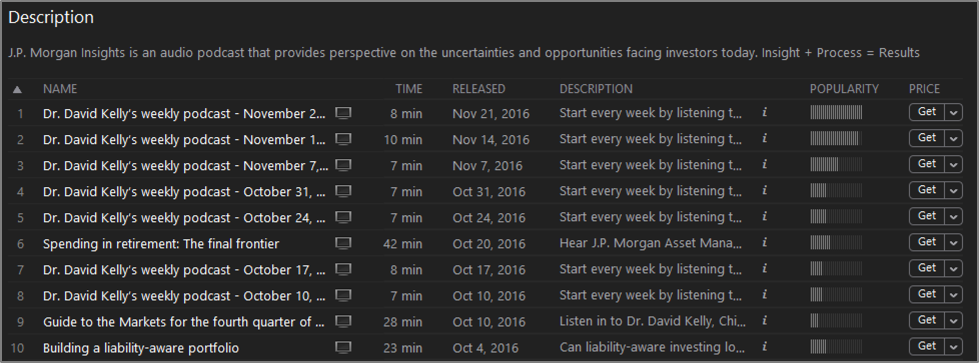

The answer turns out to be 2. Or really 1.5, because one of those is Goldman Sachs, which produces a regular podcast that is frequently unrelated to its asset management business. If you exclude them, you’re left with JPMorgan who in 2016 has produced:

- 24 audio podcasts ranging from 7 – 42 minutes, primarily focusing on insight from David Kelly

- 24 video podcasts that run the gamut from short marketing messages to video commentary

Two other top 20 firms published and abandoned podcasts over the course of the past year. It’s pretty clear to me that podcasts fall short as a useful marketing tool for asset managers, and I see two simple reasons why:

- Heavily Scripted Content is Boring: Podcasting is, generally, a platform that thrives on the energy and interactivity of the hosts. Within our industry, however, it’s easy to tell almost immediately that there’s an iron-clad script driving the conversation. The energy of a legitimate give-and-take or engaging monologue is all but absent.

- The Lack of Visuals is a Disadvantage: Discussing the markets and investments is typically data-intensive. Data-intensive conversations are best supported at least in part by visuals (graphs, charts, tables, etc.), none of which translate to an audio-only medium. Therefore an asset management podcast is usually mentally taxing to track.

So it is time to give up on podcasting? I do believe that the best answer is a simple YES. However, for those still inclined to pursue it, there are two avenues to consider:

- Focus on Non-Investment Content: Hands-down the best industry podcast I’ve listened to is this JPMorgan episode on the spending habits of retirement plan participants. Unburdened by the careful avoidance of investment recommendations, the two hosts are actually able to have a real conversation that includes banter and personality. It strikes me that broader value-add is a better opportunity than hard-hitting investment insight.

- Consider a Brand-Building Approach: Prudential produces a paid podcast via Slate as part of a broader marketing effort. While not a perfect analogy for intermediary-focused asset managers, the Prudential effort points to the potential feasibility of leveraging sponsorship and the $35 million podcasting advertising market[2] as a means to build overall brand awareness. This has some appeal at a time when many firms are at least thinking about how to strengthen their images among individual investors.

I value a contrarian perspective as much as anyone, but aside from the two just-noted considerations I think the industry can leave the “opportunity” of podcasting alone.