Is Originality Important When it Comes to Content?

Three semi-quick steps to get to my answer…

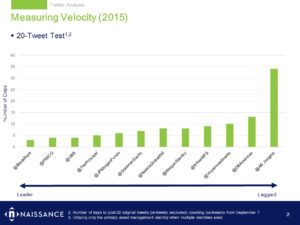

1. I tweet very infrequently.

2. The reasons I don’t tweet are multiple and common. But one of them is relevant to the question at hand: I don’t want to say something or make an observation that has already been made thousands of times before.

Case in point: my tolerance for spicy food has grown with age. So, as part of a recent Thai food order I upped the spiciness. Before the food arrived I started to wonder how I’d react to it. My thought process quickly went:

At this point I had a few version of a “spicy / Ark of the Covenant” tweet in my head. Still, as I considered putting it out there one thought popped into my head: has somebody said this before?

3. I assumed the answer to my question was YES, but a quick search showed that instinct to be mostly incorrect. It’s only appeared a handful of times over the years (at least on Twitter). Even so, my hesitation got the best of me and the world was deprived of another tweet.

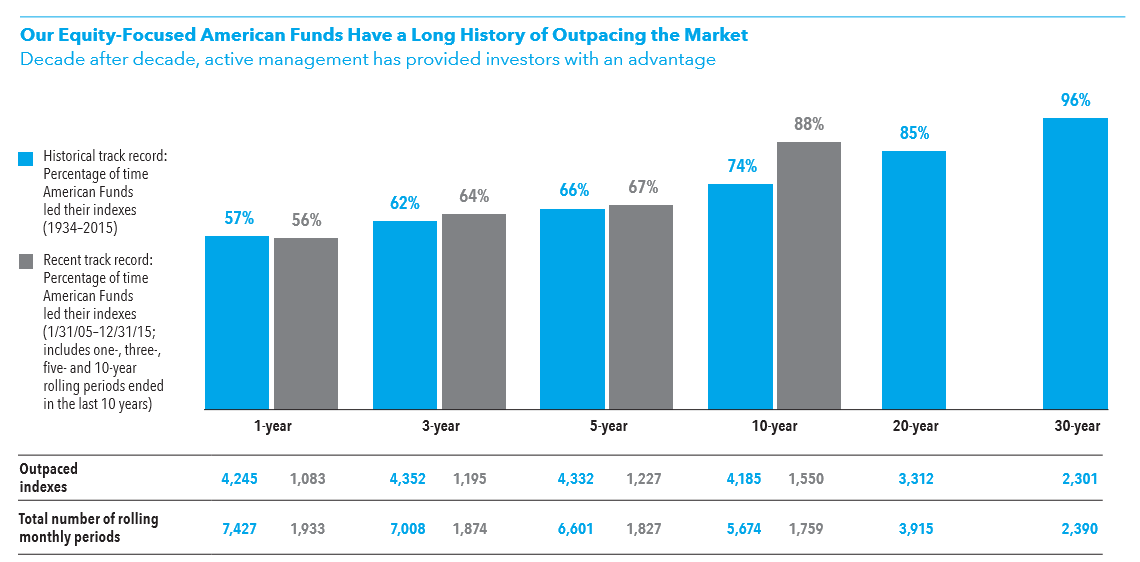

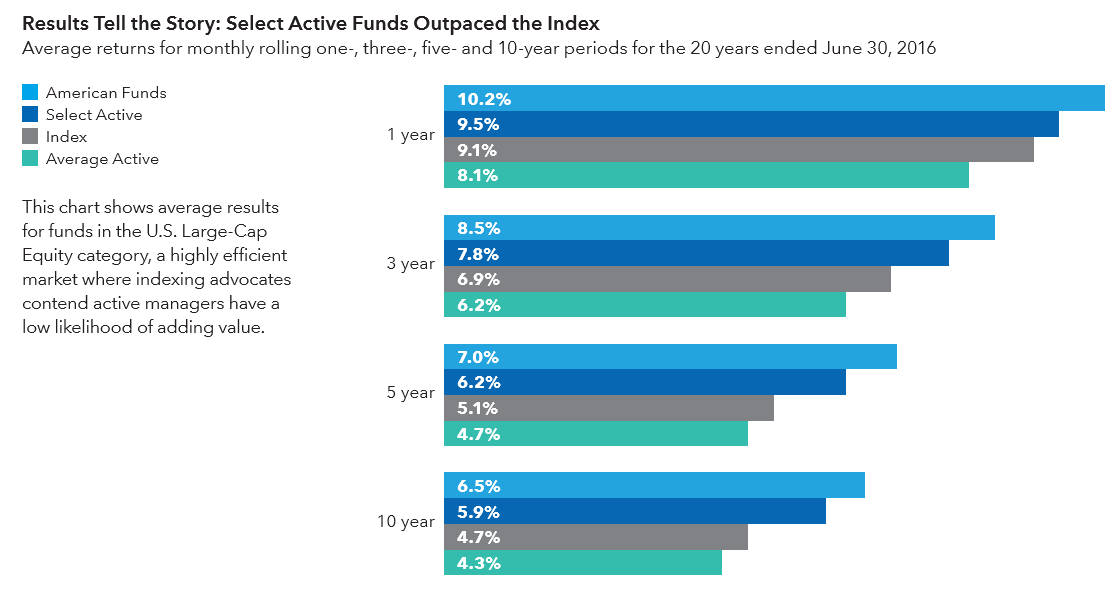

All of this made me wonder about the importance of content originality within asset management. And in a nutshell I came to conclusion that it’s just not very important at all. The most direct illustration I can point to is the defense of active management. Consider that:

- The current environment has led many, many, many, many firms to communicate a case for actively-managed investments.

- These cases overlap significantly, making highly-similar points.

Despite the ubiquity and similarity we have been working with a client this month on how to message active management. And I think our client is absolutely right to pursue this effort. Why? First, it boils down to a numbers game:

- Asset management is fractured, in that there are large numbers of providers and a huge number of clients.

- This leads to kinetic content consumption. The likelihood of any given client encountering and consuming a single piece of content from an asset manager is low. The likelihood that they will consume content on the same subject from multiple managers is even lower. In other words, content sameness has a limited chance of being noticed.

Second, multiple perspectives are sought out by thoughtful clients. So, even if someone encounters the same ideas from multiple firms, minor nuances can stand out and be memorable.

And finally, going down heavily-traveled content roads is necessary because clients expect a firm to have something to say. For example, what active manager can afford NOT to have a strong case for active management in today’s climate? Ditto meaningful topics like Brexit, the Fed’s plans for rates, and more.

In an era where firms compete not only on product and performance but on the scale and quality of their ideas, covering the most important ideas and topics is crucial while pure originality is simply a nice-to-have.